It is beneficial for scholars of any field to understand the origin and evolution of their field of study. This article is Chapter 1 of our Services Brand Management book, courtesy of the authors. This article explores the history, evolution and renaissance of brands and branding.

Because there is no clear consensus regarding definitions of branding terms, the basic terms are introduced for consistency, clarity and context, as these terms are used in this book. Brands and brand management have emerged as important research areas within the academic marketing literature;1 therefore, the concepts of brand management and the benefits of brands are also explored.

Branding history

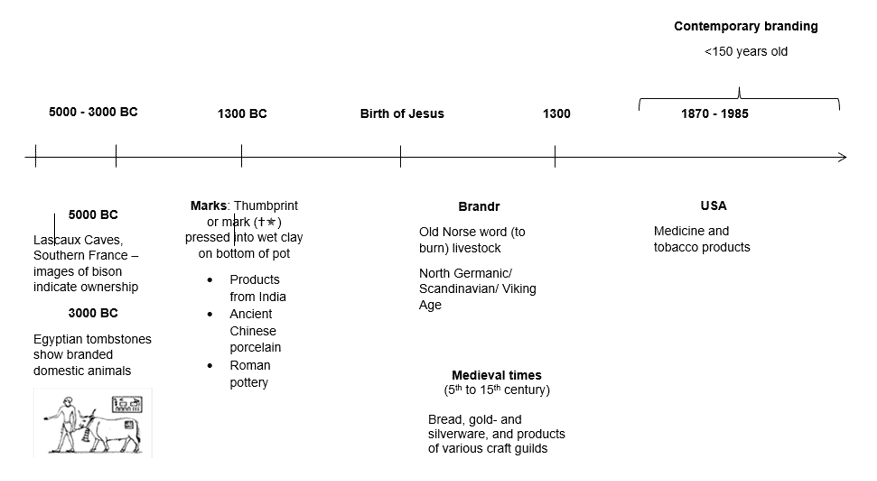

The term ‘brand’ is derived from the Old Norse word ‘brandr’, which means ‘to burn’. This was how livestock was marked for ownership identification by burning a letter, image or symbol into their hides.2

Branding has been practised for centuries, as depicted in Figure 1.1. As far back as 5000 BC, the inhabitants of the Lascaux Caves in Southern France painted images of bison on the walls to indicate ownership. Egyptian tombstones from 3000 BC show branded domestic animals.3

Later, craftsmen marked their products so that customers could identify the origin. Marks were found on ancient Chinese porcelain, Roman pottery, and products from India dating as far back as 1300 BC.

During medieval times, marks of ownership were added to bread, gold and silverware (denoting the owner’s identity or the quality of the metal used) and products of various craft guilds. The reasoning was twofold: on the one hand, to increase demand by customers who would be able to identify the origin of quality products, and on the other, to identify products of inferior quality.

Europeans took the practice of branding with them when they moved to North America. The pioneers of commercial branding in the USA were producers of medicine and tobacco products. These products furthered the use of individual packaging with distinctive labels, and the tobacco producers steered towards developing creative names to differentiate their products.4 A summary of an article by Low and Fullerton follows to provide a concise historical overview of the development of branding, providing a context for the field of study.5

The establishment of manufacturer brands in America: 1870 to 1914

The key events listed below created a fertile environment for branded products to establish distinct brand identities, leading to producers taking responsibility for their products for the first time. What happened was:

- Regional and national distribution were made easier by developments in transportation (the railroad system) and communication (telegraph and telephone).

- Production process improvements enabled the manufacture of good quality products.

- Improvements in packaging made individually packaged and branded (as opposed to bulk) goods viable.

- Developments in US trademark law from 1870 to early 1900 made trademark protection possible, which enhanced brand awareness.

- Advertising was more broadly accepted and used on a wider scale.

- Magazines became a vehicle for brand messages, owing to the realisation of increasing revenue.

- The increased prevalence of retail stores and the establishment of new types of organisations, for example, mail-order shopping, established a consumer culture.

- An increase in standards of living for Americans was brought about by industrialisation, which facilitated consumerism.

- Poor quality unbranded goods and their proliferation created initial demand for branded goods, which promised more consistent quality.

These factors enabled the spread of more affordable and better-quality products over larger geographic areas while packaging and trademark protection advanced decommoditisation. Expanded and improved communication led to a better informed and expanding pool of potential customers who were aware of the differences between products. The increased availability of products and financially able customers set the scene for mass-marketed brands.

The figure below displays a historical branding timeline.

Branding historical timeline

Source: Adapted from Interbrand, Lowe & Fullerton, and Affinity Advertising2,3,4

Branded products, however, were not without their detractors. Due to the influence of the distribution system, wholesalers, retailers and consumers initially resisted branded products. In time, however, most of the resistance in the distribution system was overcome through collaboration, authority, and push-and-pull marketing strategies.

Leadership of mass-marketed brands: 1915 to 1929

A classic research study by Hotchkiss and Franken, cited in Low and Fullerton,6 showed the value of brands. The research measured unaided brand recall (brand familiarity or awareness) across 100 categories. Some brands listed (including Ford, Colgate, Kellogg’s and Goodyear) are still well known today. The researchers remarked that the goodwill of some of the brand names was worth millions of dollars and was among the companies’ most important assets. They also observed that customers differentiated between brands as part of the decision-making process and trusted brands for quality and service.

It is interesting to note that some companies have adopted strong product brand names as company names, e.g., Chanel, BMW, and Apple, among others. Perhaps this was an early tendency towards what is presently called family or even corporate branding.

Furthermore, the functional management system, where more than one functional manager was responsible for brand decisions, became problematic. The situation was exacerbated by brand proliferation. A summary of the research is included below.

Challenges faced by mass-marketed brands: 1930 to 1945

This period included the Great Depression and World War II. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 brought renewed challenges to mass-marketed brands. Power in the distribution system moved to retailers and wholesalers, who responded to the consumer spending crunch by introducing cheaper house brands and reducing the range of brands carried.

Customer suspicion regarding advertising added to the challenges of mass-manufactured brands. Around 1930, the US retailer Proctor and Gamble began to develop a system of assigning one brand manager to a single product and even developed different personalities for their competing brands, for example, Camay and Ivory soaps.

Brand cannibalisation may be a factor to consider with this type of strategy. Competitors were slow to introduce this system, and Proctor and Gamble sustained their presence owing to a lack of competition. Interestingly, the brand manager system was mostly confined to the business-to-business (B2B) market instead of the consumer-goods market.

The dominance of the brand management system: 1946 to 1985

As the war ended, there were two schools of thought. One proposed that manufacturer-branded goods would struggle to return to their former dominance as consumers were no longer in the habit of purchasing branded products. In contrast, the other foresaw a surge in demand for branded products owing to the fundamental tenets of branding: consistent quality and manufacturer responsibility.

Moreover, during the baby boomer era, demand for branded products increased rapidly due to increased discretionary income, an extended variety of products, and the effect of television advertising.

As a result, by 1967, brand managers had become the norm at major US consumer goods manufacturers. Brand proliferation and complex organisational structures contributed to adopting the brand management system. The changes made it nearly impossible for a marketing head to understand and manage all the different products within such a complicated structure. The brand management system and brand manager concept fed into the marketing concept.

There were exceptions. PepsiCo discontinued the brand manager concept, while some companies modified their brand manager system. Some scenarios presented included companies that could do without brand managers if the company had a limited number of brands and a history of focused family branding.

One of the primary reasons for the problems experienced with the brand management system was the misalignment of authority and responsibility of the brand manager. Interpersonal skills were therefore found to be vital for success.

The future of the brand manager was brought into question. The contemporary organisational structure was substantially different from what it was immediately after World War II. Then, brand managers were the norm, owing to innovations such as downsizing, outsourcing and corporate re-engineering.

Other reasons for opposing the brand manager concept included a disproportionately internal focus by brand managers, short job tenures, a short-term approach, and deproliferation.

It is interesting to note that most of the leading brands in 1923 are still leaders today; hence the brand manager function should be retained, but with specific adaptations, which include the following:

- longer job tenures;

- more experienced brand managers;

- responsibility for a portfolio of brands;

- greater external communication and contact;

- customising the brand manager role to better align with organisational needs; and

- realising the entrepreneurial potential of the brand manager – flexibility, creativity, and relationship-building skills.

Evolution of branding

Extending the history of branding, it is believed to be as old as human society and has transitioned from the term ‘ancestral’ brands to ‘modern civilisation’ brands.7 Social development creates the need to mark objects with symbols for differentiation and identification.8 This is elementary or crude branding.

In this regard, it can be argued that branding is a social phenomenon that has transformed from an ancient practice into a multidimensional discipline over centuries.9 Central in the history of branding is the burning or marking of objects, both for commercial (product provenance clarification) and cultural purposes.

Although it has been asserted that branding is as old as humankind,7 the earliest documented history of branding in South Africa only dates back to the 1600s.10 Nevertheless, one cannot refute the possible existence of this practice in South Africa before the 1600s, mainly because of the correlation between the origins of branding (cattle ranches) and the farming lifestyle of the earliest inhabitants of South Africa, the Khoisan people.11

The evolution of branding in the South African context can also be attributed to a political paradigm shift due to the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in 1652. His successor, Simon van der Stel, established South Africa’s oldest recorded continuous brand, Groot Constantia.12 Many other South African brands established between the 1800s and early 1900s, notably PPC, Old Mutual, Rhodes University and the African National Congress, are still dominant in the country today.

Branding renaissance

Branding began as a tool to mark ownership and communicate trust, quality and cultural meaning that is transactional and transformational.13 However, due to the emergence of global commerce characterised by intense competition, branding has evolved to serve two fundamental purposes: differentiation and identification.14

The purpose of branding is twofold. Organisations need to differentiate themselves from competitors, while consumers need to identify brands to satisfy their needs and wants.15 Thus, on the one hand, brand differentiation occurs when an organisation communicates what it is and what it stands for to create and maintain favourable relationships with stakeholders.

On the other hand, brands facilitate consumer decision-making by indicating differences between ostensibly identical products.16 However, the question arises whether brand differentiation alone is adequate to derive a sustainable competitive advantage. Moreover, do consumers merely seek to identify their brands of choice, or is this an emotional and/or rational purchasing process?

Eliciting consumers’ emotional responses during brand encounters may yield a competitive advantage, particularly in exceedingly competitive business environments.17,18 Furthermore, this emotional connection may create consumer emotional value and subsequent brand attachment and loyalty.19 In this regard, brand trust is an antecedent to brand attachment and loyalty.20

This notion suggests that a positive relationship exists between brand trust, brand loyalty, brand attachment and purchase intention. However, it remains debatable whether trust alone can guard against brand switching. Conceptualising brands and brand management may clarify antecedents of brand switching.

Conceptualising branding

Academics and practitioners have widely debated brands and branding and thus, their definitions are nuanced. Kamboj et al. distinguish between brand and branding insofar as the former reflects views that reside in consumers’ minds, while the latter is a practice and a process.21 Branding is thus a complex phenomenon arising from interactions between various stakeholders.22

A brand can be a name, term, design, symbol or any feature that differentiates a seller’s products from competitors.23,24 It starts with a company or product carrying a brand name,25 but a brand also brings together and articulates company values, internally and externally; therefore, it is the external expression of what an organisation does and stands for internally.26

However, the question arises whether branding as a process should be confined to company-based architecture. This is because consumers are also brand co-creators. Nonetheless, the view held in this book is that branding is the art of aligning what an organisation wants people to think about it (brand identity) with what people actually think about it (brand image). However, delineating brand and branding outside the broader marketing discourse would be myopic.

Brand, branding and brand management

Brand, branding and brand management are discussed in this section. In addition, a more comprehensive glossary of terms and concepts is presented after Chapter 10 in the Services Brand Management book.

Brand

If this business were to be split up, I would be glad to take the brands, trademarks and goodwill and you could have all the bricks and mortar – and I would fare better than you. – John Stewart, former Chairman of Quaker Oats27

While the term ‘brand’ is prevalent in academic literature, its meaning is not agreed upon.1 A relatively recent attempt at defining a brand, based on an analysis of various explanations of the term, is “an identifiable kind of good and/or service commodity comprised of differentiated characteristics”.28

A similar definition is that a brand is a “name, sign, symbol or design which identifies the goods and services of one seller and differentiates them from those of competitors”.29 For a consumer, a brand contains a promise of performance and value, which allows consumers to project their self-image.

Kapferer speaks of “brands as living systems made up of three poles: products or services, name and concept”.30 Kapferer asserts that a brand cannot exist without an offering. This offering is identified through a name and proprietary signs and is differentiated based on tangible and intangible associations, constituting the brand’s value proposition. The intangible aspect gives brands value, without which a brand is worthless.31

De Chernatony considered the evolution of the definition of the term ‘brand’ and concluded that, at a basic level, a brand could be defined as “a cluster of values that enables a promise to be made about a unique and welcomed experience”.32 These values are initially functionally oriented but are enhanced with emotionally oriented values, adding to the promise that adds value to all stakeholders.

Based on these definitions, we understand ‘brand’ to mean: a consumer’s perception (brand image) and attitude, which comprise the tangible and intangible (attributes, benefits and psychological/emotional) associations that are used to identify and differentiate an offering (adapted from Keller).33

Branding

Branding is the strategic process and creative practice of developing a brand.34 It is the process of endowing offerings with the power of brand equity, so the branding process aims to create brand equity.35

Brand management

Brand management is the process of managing an organisation as a brand and an organisation’s brand(s) to preserve and enhance brand equity.

Brand, branding and brand management elaborated

The marketing battle will be a battle of brands, a competition for brand dominance. Businesses and investors will recognise brands as the company’s most important assets. This is a critical concept. It is a vision about how to develop, strengthen, defend, and manage a business …. It will be more important to own markets than to own factories. The only way to own markets is to own market-dominant brands. – Larry Light 36

The American Marketing Association defines a brand as a “name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or combination of them, intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of the competition”.24

A brand is more than an offering. Undifferentiated and unbranded offerings that satisfy the same need are called commodities. A brand, however, can differentiate a commodity. Also, “a brand … resides in the minds of consumers”.37 Landa calls a commodity a “parity good or service – products that are equivalent in value” and states that all offerings are commodities without a brand name.38

Differentiation may be based on an offering’s attributes or intangible feelings about and attitude towards the brand. Therefore, the brand can create a competitive advantage through differentiation by innovating and/or creating a favourable image, which creates brand loyalty.

Brand loyalty could lead to financial gains, and it is this ability of brands that makes them the most valuable assets of an organisation. Furthermore, a brand is the primary asset of an organisation and can be more important than “the bricks and mortar – or even people”.39 Muylle et al. view brands as “long-term assets that accumulate meaning for customers over time”.40

The Collins Dictionary of Marketing defines a brand as:41

A combination of attributes that gives a company, organisation, product, service concept, or even a person, a distinctive identity and value relative to its competitors, its advocates, its stakeholders and its customers. The attributes that make a brand are both tangible and intangible: a name, a visual logo or trademark, products, services, people, a personality, reputation, brand loyalty, mental associations, culture and inherent values which, together, create a memorable, reassuring and relevant brand image in the eye and mind of the beholder.

According to the Collins Dictionary of Marketing, the consumer-brand relationship is often emotional rather than rational. A strong brand elevates a brand’s position in the customer’s mind to become part of the evoked set (top-of-mind list of products), which facilitates brand loyalty.42 This builds brand awareness. Landa conceptualises a brand as the sum total of all functional and emotional aspects, the identity and consumer perceptions of and about an offering or organisation.38

Branding refers to the strategic process and creative practice of developing a brand.34 Similarly, branding has to do with creating meaning from the articulation and communication of the brand.28 Branding is a strategy to achieve marketing objectives and influence consumer preference. Branding techniques include “crafting a memorable and compelling brand name, attractive package design, and recognisable logo and symbol to evoke positive consumer responses”.43

Earlier, Fournier contemplated that in a post-modern society, brands may also fill a void in people (the “empty selves”) created by the diminishing sense of community with others and loss of traditions.44 A brand then signals to others who the person is and what the person believes. The brand then gives the person access to a brand community and provides some stability in an ever-changing world.

In South Africa, for example, at FirstRand, the organisational structure was amended to introduce a brand director as the guardian of FirstRand’s FNB, RMB, WesBank and Momentum brands, demonstrating the importance of brands to FirstRand.45 The term ‘guardian’ is preferred here because ‘brand custodian’ is reserved for the most senior position in any organisation. The brand custodian may, for example, be the chief executive officer or the managing director.

Even though strategy is at the core of the brand, any brand is susceptible to poor brand management, regardless of a brand’s strength. In addition, contemporary brand management may be more challenging than ever. Knowledgeable consumers, brand proliferation, media fragmentation, increased competition, increased costs, and greater accountability contribute to the difficulty.

Effective brand management is a long-term imperative, which is under pressure from the short tenures of chief marketing officers, an average of 23 months in the US. These short tenures may lead to a short-term profit maximisation focus, which may compromise long-term imperatives.46

Benefits of brands

A product is something that is made in a factory; a brand is something that is bought by a customer. A product can be copied by a competitor; a brand is unique. A product can be quickly outdated; a successful brand is timeless

– Stephen King, WPP Group, London47

For consumers, a brand contains a promise of performance and value, which allows them to project their self-image.48 In these instances consumers are willing to pay a premium to acquire brands to capitalise on intrinsic brand equity.

Some of the benefits of brands for consumers include that brands:50

- identify the source or manufacturer of the product;

- assign responsibility to the manufacturer;

- reduce the risk involved in a transaction;

- reduce the search cost;

- entail a promise by the manufacturer;

- are symbolic; and

- are an indication of quality.

Some of the benefits of brands for intermediaries or resellers include:

- connecting manufacturer to intermediary, and building trust between the parties;51

- less vulnerability to competitive marketing actions or marketing crises;52

- enhanced consumer interest; and

- greater profits through price premiums.53

A brand can be a key success factor for organisations because it can increase recognition and patronage.54 B2B brands create competitive advantage,52 and prominent B2B brands can command a price premium and improve relationships.55

Summary

Branding has a long history, dating back to 5000 BC when the inhabitants of the Lascaux Caves in France marked ownership by painting images of bison on the walls. As people began to produce more goods, branding became a way to indicate origin and quality. In North America, pioneers in branding were producers of medicines and tobacco who differentiated their products through individual packaging and creative names.

From 1870 to 1914, a favourable environment for branded products was created through advancements in transportation, communication, packaging, trademark protection, and advertising. This led to the establishment of manufacturer brands in America.

Branding is a complex phenomenon shaped by interactions between companies and consumers. A brand is more than a name, term, design or symbol; it includes features and benefits that differentiate a company’s products and communicates its values. A brand is seen as a consumer’s perception and attitude, a cluster of values that enables the promise of a unique and welcomed experience.

Brands differentiate from competitors through communication, and brands can elicit emotional responses from consumers, leading to brand attachment, loyalty, and competitive advantage. Trust is a key component of brand loyalty, but it remains uncertain if trust alone can prevent brand switching. Brands are important assets for companies and are more valuable than ownership of physical assets.

How to create a brand strategy blueprint

After reading this article or the free flipbook of Chapter one of our Services Brand Management book you will have an exceptionally detailed understanding of the history of brands and branding.

The next logical step is to gain an understanding of how to create a brand strategy.

Best brand strategy books

For more books about branding see the list of Best brand strategy books: 12 lessons from 12 brand books

The list include these books that I use as a brand strategist and academic:

- Start With Why

- Find Your Why

- The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding

- Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind

- Building a StoryBrand

- Marketing Made Simple

- ZAG

- The Brand Flip

- Steal Like an Artist

- Strategic Brand Management

- Services Brand Management

- Design and Identity

Frequently asked questions

Q: What is the history of branding?

A: The history of branding can be traced back to ancient times, with evidence of branding in ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley. However, the concept of modern branding as we know it today began to emerge during the Industrial Revolution.

Q: What is brand strategy?

A: Brand strategy refers to the long-term plan that a company develops to establish and maintain a successful brand. It involves defining the brand’s purpose, target audience, value proposition, and positioning in the market.

Q: What is brand identity – as in brand visual identity?

A: Brand identity refers to the visual, verbal, and experiential elements that make up a brand. This includes the brand’s name, logo, colors, typography, messaging, and overall look and feel.

Brand strategic identity is something completely different.

Q: What is brand image?

A: Brand image is the perception that consumers have of a brand. It is influenced by various factors including advertising, brand messaging, customer experiences, and the brand’s reputation.

Q: What is brand personality?

A: Brand personality refers to the human characteristics or traits that are associated with a brand. It helps to create a connection between the brand and the target audience by giving the brand a distinct and relatable identity.

Q: Who is a marketer?

A: A marketer is a person or a group of people responsible for promoting and selling a product or service. They develop marketing strategies, conduct market research, and implement marketing campaigns to reach and engage with the target audience.

Q: What is modern marketing?

A: Modern marketing refers to the practices and techniques that are used in today’s digital age to promote and sell products and services. It often involves utilizing digital channels such as social media, email marketing, and online advertising.

Q: What makes a strong brand?

A: A strong brand is characterized by its ability to create a positive and lasting impression on consumers. It is built on a clear brand strategy, consistent brand messaging, excellent customer experiences, and a strong brand image.

Q: What is the significance of branding in ancient Egypt?

A: In ancient Egypt, branding was used as a way to identify products and differentiate them from others. Various symbols and markings were used to indicate the quality and authenticity of goods.

Q: How has branding evolved in the digital age?

A: In the digital age, branding has become more complex and dynamic. With the rise of the internet and social media, brands must now actively manage their online presence, engage with customers on multiple channels, and adapt to the fast-paced nature of digital marketing.

Get the free flip book.

List of references

- de Chernatony, L. 2009. Towards the holy grail of defining ‘brand’. Marketing Theory, 9(1): 101-105. Available: DOI: 10.1177/1470593108100063.

- Interbrand. 1992. World’s greatest brands: an international review. London: Wiley, p. 8.

- Affinity Advertising. 2011. The encyclopaedia of brands and branding in South Africa. Auckland Park: Ken Wilshere-Preston, p. 7.

- Low, G.S. and Fullerton, R.A., 1994. Brands, brand management, and the brand manager system: a critical-historical evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2): 173-190, p176. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379403100203.

- Low, G.S. and Fullerton, R.A., 1994. Brands, brand management, and the brand manager system: a critical-historical evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2): 173-190. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379403100203.

- Low, G.S. and Fullerton, R.A., 1994. Brands, brand management, and the brand manager system: a critical-historical evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2): 173-190, p178. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379403100203.

- Moore, K. & Reid, S. 2008. The birth of brand: 4000 years of branding. Business History, 50(4): 419-432, p. 430-431. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802106299.

- Starcevic, S. 2015. The origin and historical development of branding and advertising in the old civilisations of Africa, Asia and Europe. Marketing, 46(3): 179-196, p. 192. Available: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2737046.

- Bastos, W. & Levy, S.J. 2012. A history of the concept of branding: practice and theory. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(3): 347-368, p. 347. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501211252934.

- Morris, M., Krige, B., Koppehel, C., Penstone, K., Witepski, L. & du Chenne, S. 2011. History of brands and branding: from Groot Constantia to Google: 1658 to 2010: A colourful history of brands and branding in South Africa. Johannesburg: Affinity, p. 5.

- Media Club South Africa. n.d. The history of South Africa. http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/sport/35-culture/culture-bg/104-history. Accessed: 7 February 2019.

- Morris, M., Krige, B., Koppehel, C., Penstone, K., Witepski, L. & du Chenne, S. 2011. History of brands and branding: from Groot Constantia to Google: 1658 to 2010: A colourful history of brands and branding in South Africa. Johannesburg: Affinity, p. 12-13.

- Bastos, W. & Levy, S.J. 2012. A history of the concept of branding: practice and theory. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(3): 347-368, p. 352. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501211252934.

- Moore, K. & Reid, S. 2008. The birth of brand: 4000 years of branding. Business History, 50(4): 430-431, p. 430-431. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802106299.

- Keller, K.L. 2013. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 4th edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, p. 34.

- Kastberg, P. 2010. What is a brand? Notes on the history and main functions of branding. Language at work – Bridging theory and practice, 5(8): 1-3. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/law.v5i8.6184.

- Candi, M. & Kahn, K. 2016. Functional, emotional, and social benefits of new B2B services. Industrial Marketing Management, 57: 177-184. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.02.002.

- He, J., Haung, H. & Wu, W. 2018. Influence of inter-organisation brand values congruence on relationship qualities in B2B contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 72: 161-173. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.02.015.

- Koronaki, E., Kyrousi, G. & Panigyrakis, G.G. 2017. The emotional value of arts-based initiatives: strengthening the luxury brand-consumer relationship. Journal of Business Research, 85: 406-413, p. 411. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.018.

- Kamboj, S., Sarmah, B., Gupta, S. & Dwivedi, Y. 2018. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: applying the paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. International Journal of Information Management, 39: 169-185, p. 174. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.001.

- Kamboj, S., Sarmah, B., Gupta, S. & Dwivedi, Y. 2018. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: applying the paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. International Journal of Information Management, 39: 169-185, p. 172. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.001.

- Wider, B., von Wallpach, S. & Muhlbacher, H. 2018. Brand management: unveiling the delusion of control. European Management Journal, 36(3): 301-305, p. 304. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.03.006.

- Fishman, A., Finkelstein, I., Simhon, A. & Yacouel, N. 2018. Collective brands. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 59: 316-339, p. 316. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2018.03.002.

- American Marketing Association. n.d. The universal marketing dictionary. Marketing Accountability Standards Board. Available: http://www.marketing-dictionary.org/ama Accessed: 4 October 2015.

- Wider, B., von Wallpach, S. & Muhlbacher, H. 2018. Brand management: unveiling the delusion of control. European Management Journal, 36(3): 301-305, p. 301. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.03.006.

- Richards, B. 2009. The fine art of branding. Available: https://thebigidea.nz/stories/brian-richards-the-fine-art-of-branding. Accessed: 8 February 2019.

- Gutting, D. n.d. From Quaker Oats to Chick-fil-A: brand relevance in the network economy. Little Black Book. Available: https://www.lbbonline.com/news/from-quaker-oats-to-chick-fil-a-brand-relevance-in-the-network-economy. Accessed: 19 September 2023.

- Pike, A. 2013. Economic geographies of brands and branding. Economic Geography, 89(4): 317-339, p. 334. Available: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12017.

- Kotler, P. & Armstrong, G. 2010. Principles of marketing. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, p. 255.

- Kapferer, J-N. 2008. The new strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term. 4th edition. London: Kogan Page, p. 12.

- Taylor, S.A., Celuch, K. & Goodwin, S. 2004. The importance of brand equity to customer loyalty. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 13(4): 217-227, p. 227. Available: https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420410546934.

- de Chernatony, L. 2009. Towards the holy grail of defining ‘brand’. Marketing Theory, 9(1): 101-105, p. 104. Available: DOI: 10.1177/1470593108100063.

- Keller, K.L. 1993. Conceptualising, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1): 1-22, pp. 2-5. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101.

- Swystun, J. Ed. 2007. The brand glossary. Interbrand. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 20.

- Keller, K.L. 2013. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 4th edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, p. 57.

- Aaker, D.A. 1991. Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

- Keller, K.L. 2013. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 4th edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, p. 31.

- Landa, R. 2006. Designing brand experiences. Boston: Wadsworth, p. 4.

- Aaker, D.A. 1991. Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press, p. 221.

- Muylle, S., Dawar, N. and Rangarajan, D. 2012. B2B brand architecture. California Management Review, 54(2): 58-71, p. 71.

- Doyle, C. 2005. Collins Dictionary of Marketing. Glasgow: Harper Collins, p. 38.

- Keller, K.L. 2013. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 4th edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, p. 74.

- Anabila, P. 2015. Exploring branding as a strategy to boost local rice patronage: evidence from Ghana. The IUP Journal of Brand Management, 12(1): 60-78, p. 62.

- Fournier, S. 1998. Consumers and their brands: developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4): 343-353. Available: https://doi.org/10.1086/209515.

- MarketingWeb. 2008. Available: http://www.marketingweb.co.za/marketingweb/view/marketingweb/en/page72308?oid=111147&sn=Marketingweb+detail Accessed: 20 January 2010.

- McGovern, G.J. & Quelch, J.A. 2004. The fall and rise of the CMO. Strategy + Business, 37: 44-51, p. 47.

- Aaker, D.A. 1991. Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

- Keller, K.L. 2008. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 3rd edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, p. 8.

- Aaker, D.A. 1991. Managing brand equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: The Free Press.

- Keller, K.L. 2008. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 3rd edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, pp. 17-18.

- Muylle, S., Dawar, N. and Rangarajan, D. 2012. B2B brand architecture. California Management Review, 54(2): 58-71, p. 58.

- Geigenmüller, A. & Bettis-Outland, H. 2012. Brand equity in B2B services and consequences for the trade show industry. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 27(6): 428-435, p. 432. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/08858621211251433.

- Snežana, U. & Bruno, Z. 2014. Characteristics branding & brand management in the fashion industry. Annals of the University of Oradea. Fascicle of Textiles, Leatherwork, (October 2014), 15(2): 189-194, p. 194.

- Aureli, S., Forlani, F. & Pencarelli, T. 2015. Network brand management. Issues and opportunities for small-sized hotels. International Journal of Management Cases, 17(4): 19-34, p. 19.

- Glynn, M.S. 2012. Primer in B2B brand-building strategies with a reader practicum. Journal of Business Research, 65(5): 666–675, pp. 673-674. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.010.

###